WHY DID YOU WRITE THIS IN VERSE?

by Carol Coven Grannick

Rhythms score my life, and always have. Music makes me dance or sing (my son would say that the smallest associations can get me singing a Broadway show tune). Reciting poetry moves my heart, spirit, facial expressions, and more. Long ago the percussive sound and rhythm of horses’ hooves trotting or cantering would propel me into a matching song. The swaying of a willow near water, slow opening dance of a lily, shapes of tree limbs, and resilient prairie grass are all poetry and music to me.

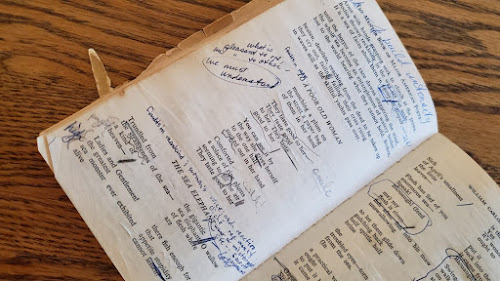

My lifelong love of poetry accompanied me from childhood, scribbling meaningful rhymes and reading Edna St. Vincent Millay and Robert Frost. I still have the old, marked up poetry anthology used for Poetry Reading competitions Illinois State Speech Contests.

In graduate school my thesis explored parallels of becoming a poet and becoming a social worker. Much of my writing, including my debut novel, REENI’S TURN, merges love of poetry and lyrical rhythms with my passion for the issue it addresses. Reeni’s story follows a tween dancer who struggles with lifelong fears and anxiety, body acceptance, and finding her own strong voice. The story’s context unfolds the diet culture’s negative impact on younger children.

It was only natural that I would write REENI’S TURN in verse.

But I didn’t. Not at first, anyway.

When the third draft sang and danced in my brain, I did the best I could to transfer it to the page. It was far from finished, and a well-published colleague told me the uncommon topic could make it difficult to publish. Occasionally, during years of revising, submitting, and putting away the manuscript for awhile, an editor or agent would ask me if I’d like to revise it in prose because “verse novels are a hard sell”. A turning point in my own journey occurred during a critique, when favorite author and mentor asked why I hadn’t written REENI’S TURN in verse.

The manuscript received some awards, went through multiple requested revisions that added content, but then hit some big bumps in the acquisitions road. My story came home to rest for again, but I couldn’t let it go. It was too important to me.

I revised REENI’S TURN repeatedly, carefully, until it became the story I wanted—an easy to read, emotionally intense, simply-plotted story of a complex experience.

After the fact, it is easy to explain why REENI’S TURN is better told, read, and received in verse. It is intensely emotional. Reeni’s fears and strengths, despair and joy, beg for lyrical language and form. With snapshots of time, space, and emotion, and white space for respite, the reader can follow Reeni’s initially-misdirected journey from shy, fearful girl to self-accepting, self-reflective, and strong, clear-voiced Reeni.

The structure of the novel in verse alternates intensity and safety for the reader, and for the character, whose all-consuming experience of body discomfort and dieting, longings and fears, self-disparagement and self-acceptance, occur within a safety net of loving parents, a wise best friend, and the still, small voice that guides her.

These are all good reasons why the book works in verse.

But, really, I wrote REENI’S TURN in verse because the language danced in my brain, the music begged for words to be attached. Reeni hears music and must dance, and her story kept calling for verse.

And much like Reeni’s response to the discovery of the “still, small voice”, I had to listen.

The Still, Small Voice

Last fall on Yom Kippur,

first time in adult services,

I held the heavy prayer book instead of stapled pages,

let my mind wander

the way it does when I’m dancing,

swaying from a long time standing,

swaying to familiar melodies of prayers.

Then these words:

The great shofar is sounded,

a still, small voice is heard.

My body stilled,

the words shivered into my heart

and through my body—brain, heart, arms and legs,

the way music does,

deep inside where it sings out,

Dance!

But instead of that,

these words whispered to me,

Listen!

©Carol Coven Grannick 2020